Published on March 17, 2014

The relatively recent tradition of American consumption of media has had the most immediate effects on influencing culture and allows propaganda of racial beliefs to be deeply rooted in society. Photography was the first use of pictorial proof as documentation of scientific analysis starting in the late 1800s. There was a sudden trust from viewers when they were presented with an image of presumed objective nature, emphasizing the ideology of “I’ll believe it when I see it.” The use of this medium on the study of human beings can be traced back to extensive works on eugenics and attempting to cite the differences between human races. It’s an imperialistic, adventurist notion to travel to new lands with the goal of discovery and the promise of riches for a return with an exotic item.

The relatively recent tradition of American consumption of media has had the most immediate effects on influencing culture and allows propaganda of racial beliefs to be deeply rooted in society. Photography was the first use of pictorial proof as documentation of scientific analysis starting in the late 1800s. There was a sudden trust from viewers when they were presented with an image of presumed objective nature, emphasizing the ideology of “I’ll believe it when I see it.” The use of this medium on the study of human beings can be traced back to extensive works on eugenics and attempting to cite the differences between human races. It’s an imperialistic, adventurist notion to travel to new lands with the goal of discovery and the promise of riches for a return with an exotic item.

Today, this need for new documentation of the found (real or fantasy) can be experienced through movies in the comfort of the home. Classic films are passed down as a form of nostalgia that function as treasured moments of time in the lives of our recent ancestors. These movies were primarily made for historic educational purposes or in response to social anxieties. The problem, however, is that some of these movies also functioned as racial propaganda. The 2005 remake of King Kong is a slight variation of the same story told in the 1933 version, but the 2005 version relies on more progressive audience sensibilities. In 2005, audiences are supposed to sympathize with King Kong. However, both versions still function as illustrations of the black consequence for touching a white woman.

The actual Classic Hollywood era started right after the Silent Era (pre-1929), which lasted from 1929 to 1945. Introducing sound to films allowed them to be more widely distributed – but to segregated theatres. The audiences of these films would be mostly white upper/middle class. Undertones of racism could be easily included and would address and enforce racial lines. According to Rice (2003), “The monster always constitutes the return of the socially or politically repressed fears of a society, these energies, memories, and issues that a society refuses to deal openly with” (p. 203).

In 1933, coming out of the World War I and the Great Depression, America was tense. Everything seemed to hang in the balance at this moment in history. Franklin D. Roosevelt was about to launch his New Deal, so the country was on the edge of either sinking farther down or rising back up. Anxieties were high among racial lines, and blame was ready to be established. This tension was perfect for a revolutionary adventure film called King Kong:

And now, ladies and gentlemen, before I tell you any more, I’m going to show you the greatest thing your eyes have ever beheld. He was a king and a god in the world he knew. But now he comes to civilization merely a captive – a show to gratify your curiosity. Ladies and gentlemen, look at Kong, the Eighth Wonder of the World.

The movie, made by Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack, is the “construction and maintenance of a racial ideology which spoke to the realities not only of domestic American politics but also to America’s global role in racial exploitation and imperialism” (Rice, 2003, p. 191). It begins with an ethnographic filmmaker named Carl Denham from New York is about to set sail to a new world. He has a “larger than necessary” vessel and is in need of a lead female, since his last movie flopped because there was a lack of romantic interest. Ann Darrow, a homeless and starving girl on the streets, is found by Denham and hired onto the movie. The crew sails to a place called Skull Island, where they stumble across a group of native islanders doing a ritual. Once they set eyes on the Golden One (Darrow), it is decided that she will be offered up as tribute instead of a girl from the tribe. The crewmen hurry and get her back on the ship, but later that night she is captured by the tribesmen.

There is a giant wall that divides the island in half. For the ritual offering, Ann is placed on the other side of the wall, tied to a stake. Out of the jungle emerges a giant ape, who takes the now unconscious Darrow back into the trees. Once Denham and the crew realize she is gone, they go back over to the island loaded with rifles and gas bombs. King Kong is not alone in his kingdom – but is accompanied by prehistoric dinosaurs. He fights each one off and is able to rescue Darrow before the crew takes her back. King Kong is furious and tries to follow, but he is overcome by the bullets and bombs. Denham then decides to take King Kong back to New York and put him on display.

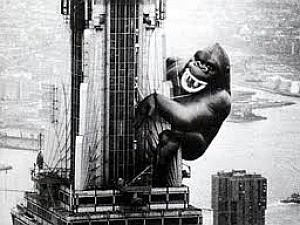

The vessel now becomes relevant as King Kong is carried in chains back to the city; the entirety of which is cut out of the movie. On the stage of a theater, he stands on a pedestal, arms spread apart by thick chains (See Figure 1).

He is able to break free and again captures Darrow – this time taking her to the top of the Empire State Building. For the first time he is overcome by the landscape and is eventually taken over by planes and falls to his death (See Figure 2).

Police Lieutenant: ‘Well, Denham, the airplanes got him.’

Carl Denham: ‘Oh no, it wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast.’

Beauty and the Beast is a fairytale that most know as Beauty falling in love with the Beast. She is able to look past his physical appearance and see his good heart. Changing fairytales to serve a particular purpose can be found in Hitler’s Mein Kampf. As a form of propaganda, he changed popular characters like the evil witch in Snow White into an old Jewish woman so that children would grow up with an underlying and potentially unexplained fear. The Grimm fairy tales were the “new Bible of the German folk education program” (Mieder, 1997, p. 162). In King Kong, the function of the Beast dying is to show consequences for touching a white woman. She is the white man’s most prized possession and will be protected at all costs from the rape of the black man.

There are many examples throughout the film that comment on the power of whites and western technology over the primitive black society. Even outside the plot of the film, King Kong was the first movie to use clay stop motion. Figures like Kong and the dinosaurs could not have been achieved without the technological advancement and the direct instruction of the white hand. Our main character, Denham, starts off with a history in the filming and selling pictures of foreign lands. He is the ethnographic observer hoping to find exotic treasure. Denham found his historic treasure in Kong, and was able to overcome him when he crossed the line “into civilization” with gas bombs.

Captain Englehorn: ‘And you expect to photograph it?’

Carl Denham: ‘If it’s there, you bet I’ll photograph it!’

Jack Driscoll: ‘Suppose it doesn’t like having its picture taken?’

Carl Denham: ‘Well, now you know why I brought along those cases of gas bombs.’

Technology serves as a way for the white man to show his mental capability overpowering the savage force of Kong. The dinosaurs on the island, along with the figure of Kong being an ape, suggest the main character to have a primitive nature. Throughout the film, he seems to just have two moods: a manic rage and a child-like curiosity. This imagery portrays blacks as stupid and submissive to the more evolved white culture. During the Depression, the Empire State Building was a large symbol of power and hope for the country, as well as being a very elaborate and expensive phallic statue for the dominant man. Kong takes up the majority of the frame in every scene until climbing this building. Finally, something is bigger than the ape: the evidence of white technological dominance. King Kong becomes a sitting target for the planes. His resistance against white male oppression knocked him down from his brief moment on top to descending below the top of Denham’s head.

The last function that can be talked about in regard to race is the role of Kong as a performer. Scenes where his large face and teeth fill the frame allude to black face. This was a costume made popular by The Jazz Singer in 1927 and worn by white men to portray blacks. Black face (See Figure 3) was a way to domesticate and consume the black man while knowing the white man is still in control. In this regard, Rice (2003) said, “Black figures were there to be looked at, shaped to the demands of desire; they were screens on which the audiences fantasy could rest … its fundamental outcome was to secure the position of white spectators as controlling figures” (p. 141).

Even having a predominantly white audience marks Kong as the other. Denham puts him on display on the stage, like black slaves were when they were being sold. During this point in history there was the Great Migration, which meant that there was a significant increase in the African-American population in New York. All of the scenes with Kong in the city specifically have no black viewers to enforce the overpowering whiteness of the city.

Theatre Patron: ‘Hey, what’s this show about, anyway?’

Theatre Patron: ‘I don’t know – they say it’s some big gorilla.’

Theatre Patron: ‘Oh, geez – ain’t we got enough of them in New York?’

America is a consumer-based society, and widespread imagery is available to be inhaled at all angles. The symbol of King Kong is well known in every household in the country. He has become an idealized image of unleashed savagery and a king brought down from his throne by greed. Of course, the amount of Americans that have actually seen the movie and known the racial implications associated with it are only a small fraction of the worldwide phenomena of Kong. For his 50th anniversary, a large balloon animal was placed on the top of the Empire State Building (See Figure 4).

Kong has been used in advertising: both for public and private use (See Figure 5). His size and strength are the only associations that stay behind (Rice, 2003).

Hooks (1992) sees that “from the standpoint of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, the hope is that desires for the ‘primitive’ or fantasies about the Other can be continually exploited, and that such exploitation will occur in a manner that re-inscribes and maintains the status quo” (p. 22). Cinema has a particular way of keeping the past incredibly close and tangible. Visual imagery, especially in movies, is able to burn into the mind like a flash of light. Once something is seen, it can never be unseen.

Fascinating cannibalism, or the “obsessive consumption of images of racialized Other, known as the primitive” (Rony, 1996, p. 7) is a grotesque way of describing this phenomena. This can be compared to the inability to look away when something horrible is happening. The abundance of media that keeps the racial border massive, not just in cinema, but in photos, memes, and much more. Since cinema has the ability to be epic, and even change lives, the stories that are chosen to pass down to future generations must be chosen wisely. One such life changing moment was experienced by director Peter Jackson, who cites King Kong as his reason for going into filmmaking. Since this was such an important moment in his life, and since he had recently reached success from his adaptation of the Lord of the Rings Trilogy, he decided to make another remake of Kong. This had been tried many times before, the story being slightly changed each time to suit different audiences.

The 1976 version of Kong, directed by John Guillermin, is the least successful direct adaptation. Other films like Mighty Joe Young directed by Ernest Schoedsack in 1949 and Ron Underwood in 1998 did not become as popular as any of the Kong films. It is interesting that one of the directors from the original Kong helped direct Mighty Joe Young, but those movies also have the white female lead fall in love with the Kong character.

The 1976 King Kong has stronger imagery of western technological power in that the white man decides to save Kong at the end when he falls by replacing his heart with a mechanical one. He now has the gift of life from the white western technology and will most likely be in his debt.

As is human nature, when something makes one feel attached or nostalgic, the impression is to keep it alive and make sure that it is passed onto future generations. Clay stop motion was such an incredible advancement in its time, but it is hard for a modern audience to not watch it and laugh. Audiences develop a critique of photographic imagery and quality that affects the overall experience. Jackson made sure that he got plenty of media to cover his personal attachment to the film, so audiences would know that he had a personal investment. There was reportedly a lost scene in the 1933 version that Jackson recreated using Cooper’s technique and methods of shooting.

Releasing this media not only got him more attention, but also bridged the gap between the original version and his own. As there are obvious racial problems with the movie, which was appropriate at that time for film to react to the current social anxieties, a remake attempts to bring those tears in our culture back to the surface. The 1976 version tried to make the story happen in the modern era, and since it was not written for that time it was not successful. Jackson had to then decide to set the film in the 1930s, which does not alleviate the historical relevance and functioning dominance of the movie (Rony, 1996).

Having viewed this movie as a child, he was now experiencing “the desire…to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly…overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction” (Rony, 1996, p. 9). Jackson attempted to change the story slightly to make it seem like the natives on the island oppressed Kong, and so he made a choice to go with Ann to New York. Already there was a problem with his depiction of the native tribesmen. When they started the ritual to deliver Ann to Kong, the natives put ape masks on their faces and, “humanity became hidden and they were one with Kong as ‘neither beast nor man’” (Rice, 2003, p. 123).

Later, when everything still goes back for Kong, and he’s dying on top of the Empire State Building, Jackson has Ann and King Kong stared at each other longingly before he falls off the side. The implication here is that they loved each other, but Beauty still killed the Beast: even if it was not intentional. Lastly, the integration of a historical film into the modern day only further enhances the dominance of western technology. The dinosaurs on the island, the city, and Kong himself are now more realistic than ever. American culture now has a sharper and slightly more violent version of the 1933 classic King Kong with the same racial undertones.

Completely changing the story has not worked out well either, especially because it was written for a certain period in time. Taking events that were relevant eighty years ago are not going to affect a modern day audience as much as it would have in the 1930s. Audiences now are much more sympathetic with Kong and see how tragic his unloved life was, instead of viewing him as a monster that was finally rid of.

As photographs and samples from foreign lands were taken as evidence of alien contact, so should the documents of past human events. Not to pretend that racism does not exist in contemporary society, but “cinematic expressions of slavery have become sedimented into a range of contemporary film narratives and genres, monster film ‘sediments’ slave experience” (Rice, 2003, p. 98). Keeping the ‘slave experience’ alive keeps racist beliefs alive, even if they are subconscious. Just like Hitler knew that replacing the villain in popular tales would have an effect on the future generation, cinema has the same effect – especially if the film, like with Peter Jackson, has had a dramatic impact on a persons’ life. Nostalgic views on the past through the lens of cultural change can provide a false sense of security in our “progressive” present.

Reference List

Dundes, A. (1966). Journal of the Folklore Institute. Vol. 3.3: 226-249.

Erb, C. (2009). Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood icon in world culture (2nd ed.) Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Hooks, B. (1992). Black looks: Race and representation. Boston: South End Press.

Mieder, W. (1997). The politics of proverbs: From traditional wisdom to proverbial stereotypes. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Rice, A. (2003). Radical narratives of the black Atlantic. London and New York: Continuum.

Rony, F. T. (1996). The third eye: Race, cinema, and ethnographic spectacle. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press,