Published on Aug. 2, 2014

Introduction

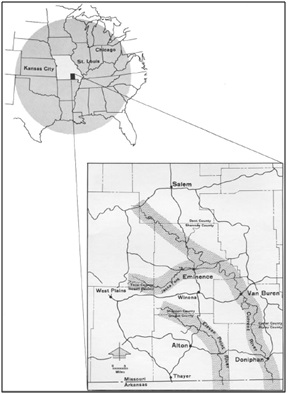

The whole place was damned from the beginning. Long before becoming a national park, the Ozark National Scenic Riverways (ONSR, Ozark Riverways, or Riverways) has been subject to intense competition and controversy. Located in southeastern Missouri, the boundaries of the ONSR comprise of parts of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. Recognized primarily for recreational floating, the property around these rivers have been fought over by numerous entities to secure invaluable resources (i.e. hydroelectric power, scenic river tourism, timber).

The historical geography of the Riverway landscape denotes a place that is complex in its political ecology, cultural landscape, and physiography. When examining a map of the national park, the ONSR looks like an unfinished puzzle: Three dispersed, disordered masses of land where millions of visitors make pilgrimages every year to camp, float the rivers, and chug alcoholic beverages. The borders of the Riverways symbolize the geographies of power and controversy that reach back before the ONSR was created. Through the 1938 Flood Control Act, the Army Corps of Engineers tried to dam the upper Current River and tame the sweeping current that coined the river’s name. In 1964, the Riverways were pardoned from being dammed, but were instead changed in other ways (Sarvis, 2002). The establishment of the ONSR on August 27, 1964 has twisted the area into a tourist trap and a political tool wielded by Congress.

On October 1, 2013, the federal government shutdown caused the temporary closing of 401 national parks (Plumer, 2013, October 4). While an inconvenience for tourists and local business owners, the 2013 federal government shutdown exposed a greater need to examine the powers that regulate national parks. This paper will incorporate historical geography, political ecology, and law to understand the geography of power of the Ozark Riverways. Taking from these approaches, the argument will be made for new sustainable forms of park management through reliance upon local knowledge and the decentralization of national park governance.

Methods: Weaving ONSR Power Geographies into Historical Geography, Political Ecology, and Law

The research for this paper consisted of conducting field surveys on the Current River, accumulating scholarly resources, reading through oral history transcripts, and collecting historical maps. This paper relies on a multifaceted method to understanding geographies of power and controversy. In this case, power and controversy are viewed as interrelated concepts that influence each other. The umbrella themes throughout the paper include historical geography, political ecology. During the research process, power and controversy have behaved as ambiguous and omnipresent within the Ozark Riverways landscape. The bibliography reflects the difficulty to pin down this topic. Authorities on the issue range from lawyers, to political ecologists, to historians, to geographers, to sociologists, and to journalists. Each discipline offers a different lens to view how the Riverways formed.

An applied historical geographic approach will be used to perform three duties: Interpret the past landscape of the Ozark Riverways, understand the park’s present state of affairs, and predict the future of the park and the affected powers. Employing legislative documents and historical archives, the following pages will detail how the landscape of the ONSR has been shaped and changed. Meinig’s (1979) various lenses of the landscape will provide a frame for the historical geographic progression of the national park. These viewpoints take account of the landscape as artifact, aesthetic, wealth, and problem.

Also, the historical geographic survey of the Riverways provides a localized perspective of the geography of power through the emphasis on oral history interviews of people involved in the Ozark Riverways. The interviews were conducted between 1997 and 1998 and supported by the Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. Along with oral histories, Sarvis (2002) was integral to constructing a chronological survey of the ONSR region. This article provided much of the background historical context on the ONSR. Similar to Sarvis (2002), Stevens (1991) depends on historical geography to examine the relationship between the core (the waters and shores of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers) and the hinterland (the peripheral area surrounding the rivers used for mining, timber extraction, railroad transport, and hunting). The geographic concept of core and hinterland concept becomes a major concept in the analysis of power’s historical reach on the ONSR landscape.

Political ecology constitutes the most significant theme interweaved through the power and controversy of the ONSR landscape. For the purposes of this paper, political ecology will be defined as the interaction between politics and the environment. The findings of this research show that power, in its various façades, is inherently political and shapes how the ONSR environment is managed. Gross et al. (2009) identifies a sense of capitalism with the development and management of national parks, using Yellowstone National Park as the case study. On the opposite spectrum, Dressler et al. (2006) analyzes new trends of decentralizing national parks in developing countries like the Philippines. Likewise, Kaltenborn (2011) explains a similar call for public participation in a national park in Norway. In sum, political ecology establishes important comparative studies of national parks and the shifting trends of power geographies.

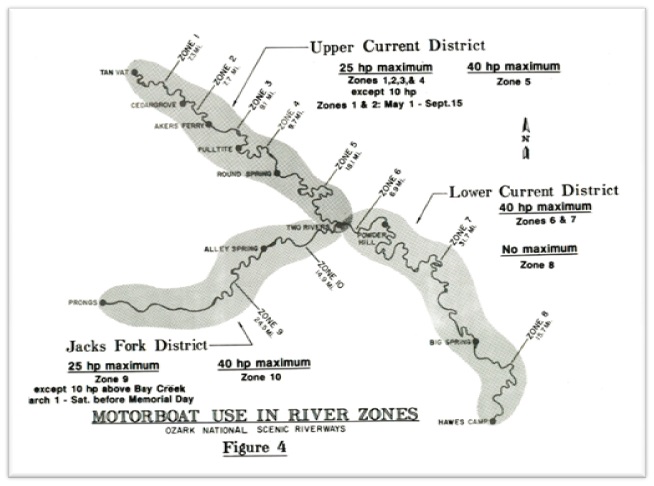

Integral to the understanding of power, particular attention will be paid to the controversies involving the legal challenges of park regulations. The main legal topics that will be discussed include: Damming of the Current River, federal land acquisition period of the 1960s and 1970s, “grandmawing” or timber theft, extraction of the land’s feral horses, illegal canoe rental businesses, boat horsepower restrictions on the rivers, and trapping on park lands.

The legal side forms connections between the ONSR controversies and governmental issues related to Congress, the Constitution, and conservation/preservation law. For example, law publications like Ragsdale (1991), Shepard (1984), and Hemmat (1986) address Congress’ constitutional powers in governing federal parks and conservation areas. These publications explain the scope of federal power over the ONSR. Other articles like Ragsdale (2013) and Ragsdale (2012) apply philosophy, spirituality, and the law to advocate more sustainable ways to govern federal preservation and conservation areas. These insights will provide the philosophical framework for making sense of the legal aspect of the ONSR geographies of power and controversy.

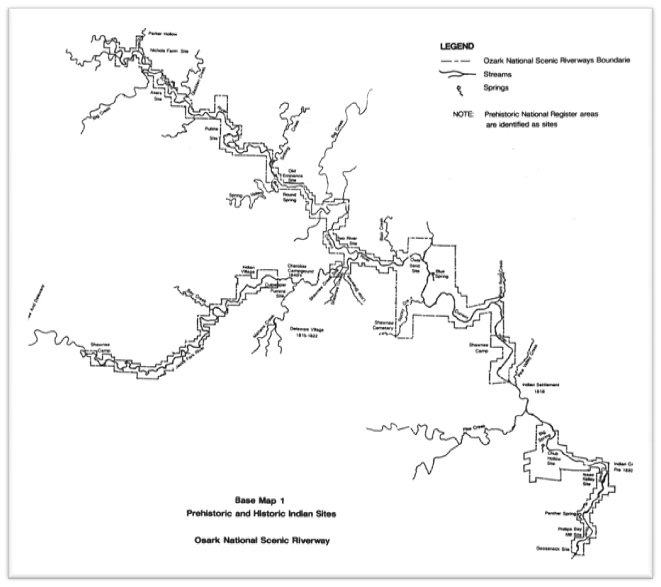

Away from the rivers, there is a definite lack of land use by the early settlers. This surrounding area is referred to as the hinterland, or the periphery. For the most part, the hinterland was used for timber harvesting and mining for lead and zinc (Stevens, 1991). In the cartography of the maps presented in this paper, the periphery tends to less illustrated, demonstrating its perceived insignificance. Conversely, the core is typically drawn in much greater detail, testifying to its importance to the map authors. The next sections will provide an in-depth investigation behind the controversy and power behind the area represented by these historic maps.

Reconstructing the Past: Physical Geography and Land Use/Land Cover

Over the centuries, the physical geography of the Riverways has changed substantially and provides an essential context for why the ONSR has been controversial. Before the arrival of the Europeans, the Ozarks used to be “open landscape described as barrens, scrub, with scattered,

thin timber on the plateaus and plains” (Harlan, 2010). Reasoning for this phenomenon is rooted in Denevan (1992) and Sauer (1944), which argue that Native Americans often set fire to the land, which augmented the presence of prairies and barren landscapes.

The forest began to take over after the Europeans began colonizing the region. Consequently, timber quickly became a traditional resource for local Ozark people to harvest for profit. Particularly, locals in the Ozarks became infamous for the illegal folk tradition called “grandmawing,” in which lumber was stolen or cut within restricted territory. When asked where they got the wood, the Ozarkans would claim that they retrieved it from their grandmother’s place (Sarvis, 2002). From controlled burns to grandmawing, humans have existed as an ever-present agent in the land use/land cover change of the Ozarks. In the 1900s, the folk forms of interacting with the environment starkly contrasted with the strict federal regulations of the ONSR.

The forest began to take over after the Europeans began colonizing the region. Consequently, timber quickly became a traditional resource for local Ozark people to harvest for profit. Particularly, locals in the Ozarks became infamous for the illegal folk tradition called “grandmawing,” in which lumber was stolen or cut within restricted territory. When asked where they got the wood, the Ozarkans would claim that they retrieved it from their grandmother’s place (Sarvis, 2002). From controlled burns to grandmawing, humans have existed as an ever-present agent in the land use/land cover change of the Ozarks. In the 1900s, the folk forms of interacting with the environment starkly contrasted with the strict federal regulations of the ONSR.

Beneath the vegetation, ridges and valleys compose the topography of the Ozark Highland region. The Current and Jacks Fork Rivers weave through the valley corridors of the landscape’s rough terrain. The sharp contrast in elevation instills a sense of concealment or isolation (Sauer, 1920).

Publications often use the topography to describe the independent, isolated persona of the native Ozarkans (Sauer, 2002). Additionally, the slanting slope of the river bottoms, especially in the Upper Current, allows them to move water at considerable rates, millions of gallons per day (Hall, 1969). The constant surge of water makes the Riverways an ideal means of transportation and recreation, yet another motivation for the fierce competition over the control of these bodies of water. In sum, the springs, rivers, forest, and the isolating terrain capture the apparent “wildness” of the Current and Jacks Fork environment and local culture.

Caves also make up an important part in the physical geography of the Riverways. Karst comprises the dominant geological feature of the ONSR physical geography. More or less, the physical landscape consists of a block of cherty limestone carved out by the underground springs and the rivers they fed. Limestone caves and bluffs are also abundant along these rivers and have been sought after by miners for lead and zinc resources (see Figure 3; Sarvis, 2002; Schuchard, 1984). Over time, the physical geography of the region has changed frequently, much like the land has changed in human use over the centuries.

Cultural Geography of the Ozark Riverways

The Current and Jacks Fork Rivers have witnessed various types of cultures in its historical landscape. The archaeology of the place alludes to the diversity of peoples that both lived and passed through the area. Human occupation of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers reaches back to the Paleo-Indian Periods. The results of an archaeological dig at Round Spring, a site next to the Current River, suggest that the Dalton people were the first to settle this region during the Late Archaic Period (Lynott, 1991). Identified by the style of projectile points, the Dalton people probably lived in this region sometime between 9250 and 7500 B.C.

The Meramec Spring culture temporarily occupied the region during the Woodland era, sometime between 600 and 450 B.C. (O’Brien and Wood, 1992). From A.D. 700 to 1200, the Mississippian and the Meramec Springs peoples were the dominant groups in the area, as indicated by analysis of the human burials and the style of earthenware ceramics (Lynott, 1991 and A Proposal, 1960). Still, the present archaeological evidence scarcely accounts for the breadth and depth of the cultures made this place home.

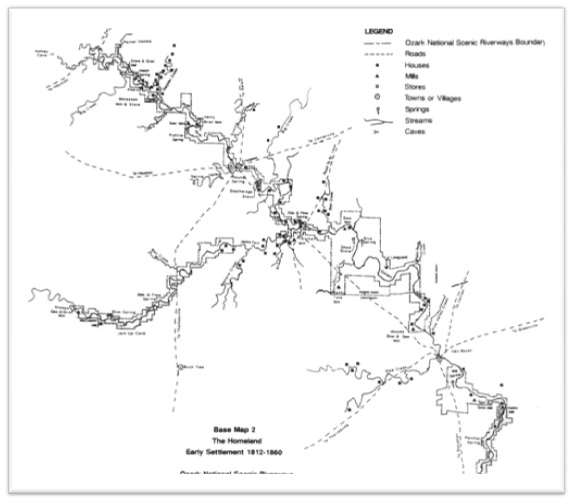

Historically, the Osage group were the first contacts for the incoming Europeans. The European survey of the region was led by Hernan De Soto, a Sixteenth Century Spanish explorer (Hall, 1969). Archaeological evidence and historical archives indicate that these indigenous peoples mainly used the land for hunting and foraging. In contrast to today’s intensive river use, the Osage mainly kept to the land and barely utilized the river for travel or fishing (Din and Nasatir, 1983). According a letter from William Clark on January 20, 1821, the Shawnees or the Delawares also might have inhabited the Riverway area during the 1800s (A Proposal, 1960). The map in Figure 6 illustrates an even dispersal of indigenous sites, some of which are identified as Shawnee and Cherokee campgrounds, along the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. Essentially, as the map validates, the Native Americans and Paleo-Indian peoples tended to establish informal, nomadic settlements within these Ozark valleys. Land use would soon shift drastically once the Caucasian settlers settled the region.

The Ozarkan Cultural Landscape

As the Native Americans of the Ozarks were forced to move onto reservations, the Caucasians from Southern Appalachia settled along the Current and Jacks Fork in the 1800s. Most of these settlers were Irish, Scottish, and English (Sarvis, 2002). In an oral history interview, Gene Brachler (21 August 1997) traces Ozark culture back to the English and Irish coming to the area from the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Kentucky. These people were the pioneering subjects that led to the creation of the Ozarkan culture. Their values stressed the need for independence, connection to the landscape, open-range grazing of hogs, and self-sufficient agricultural production (Sarvis, 2002). Land was traditionally viewed as a commons area for the community. Little importance was placed on setting up borders or the private ownership of land. By the 1900s, the Ozark culture’s strong-ancestral bonds accompanied by regional isolation created tension when government interests began to intervene.

Landscape as Problem: The Geography of Controversy in the ONSR

In the 1900s, the local connection to the land became stressed with government interests trying to control the river. In contrast to the informal, communal use of the region, territoriality soon became more significant to locals and governmental entities. During this period, a series of disputes arose over how to manage the river systems and watersheds, especially between local communities and the federal government. For example, there was a greater trend for powerful individuals and organizations to create opportunities for public recreation and tourism. By 1919, booster organizations like the Ozark Playgrounds Association and writers like Leonard Hall advocated tourism for the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. The State of Missouri reacted by creating state parks in the 1920s like Alley Spring, Big Spring, and Round Spring (Sarvis, 2002).

Conversely, the Army Corps of Engineers became an opposing power with the proposal of damming the Current River in the late 1930s. Debate over this topic continued until 1964, when the ONSR was authorized by President Lyndon Johnson as the first scenic riverway in the United States (Hall, 1969). The next pages will utilize oral histories and legislative documents to set the stage for the controversies behind these debates and the entanglement of powers that competed for control of the Riverways before the national park was established.

A Myriad of Powers: Competition for Riverfront Property

Before the establishment of the ONSR, competition for control of the Riverways territory became the prevailing problem for the local communities (i.e. Eminence and Van Buren, Mo.) as well as the local, state, and federal government. Debates and hearings were prevalent, especially during the 1940s and 1950s. While locals were confronted with questions of land and river management, various government agencies also competed with one another.

Before the ONSR was authorized, intra-governmental competition over land management transpired among the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps or Engineers), the Forest Service (USFS or FS) and National Park Service (NPS or Park Service). Drawing from Painter (2010), the concept of territoriality in this historical case implies a complex network of competing powers that try to gain control over a landscape. In 1964, the NPS became the victors and turned the area into the first scenic riverway of the United States (Sarvis, 2002).

One of the reasons for why the NPS received the Riverways stemmed from the opposition of the Corps’ proposal to dam the Current River and the nearby Eleven Point River (Hall, 1969). From the 1930s into the 1960s, the Ozark locals were polarized by their opinions of the proposal. David Dix (5 Aug. 1998), a Shannon County native, remembered that in certain parts of the area, it would be dangerous to even hint at one’s position on the damming idea. In the town of Doniphan, Mo., near the Upper Current, Dix recalled that the dam proposal “split the people” and perpetuated the worst of the “bitter fights” during this period.

On one side, some Ozarkans strongly opposed the damming of the current river. In an oral history interview, local landowner Bill Wright (5 Aug. 1998) argued that the proposed dams were caused by the ending of World War II. According to Wright, the people who were against the Corps of Engineers believed that the military “ran out of anything to do when the war ended, so they started trying to think up dams they could build.” Another local, named Gene Braschler (5 Aug. 1998), commented many of the dams that were built in the United States with the intention to create something better than what was already there. He argued that the Corps likely did not take into account for the fact that the Current River is “probably one of the most beautiful rivers in the world, one of the most unique rivers in the world—the number of springs and the fall per mile.” Likewise, there was a fear of the environmental repercussions of damming the rivers (Sarvis, 2002). As a child, David Dix (5 Aug. 1998) was told tales that a dam on the Current River could flood the courthouse yard in Eminence up to thirty feet with water. Such speculation attests to the folkloric perceptions of politics that the Ozark peoples developed regarding land management decisions.

On the other side, the case was made in support of the dam proposals. For example, Richard Ichord, before he was elected member of the 87th Congress, ran against the NPS proposal in favor of the damming. David Dix (5 Aug. 1998) paraphrased a speech Ichord once made during the Congressional elections, “I’m against any action that will make a haven for hoot owls and bobcats for a large part of my area.” Ichord’s anti-NPS position won the community over. Ironically, soon after Ichord’s election, the politician changed his position to support the Park Service plan that would create the ONSR (Sarvis, 2002).

Ichord’s change in position influenced the outcome for the future management of the Riverways. In an oral history interview, Gene Brachler (5 Aug. 1998) admitted that despite he was opposed to the NPS management of the ONSR. But, he supported the national park as a “kind of insurance to prevent the Current River from ever being dammed.” Overall, these oral history accounts testify to the ambiguity of power, the influence of key political actors, and the landscape of problems spawned by government intervention.

The Corps was not the only federal entity trying to gain control over the Current and Jacks Fork rivers. The USFS also tried to obtain the land for multiple purposes, but chiefly for harvesting timber. Conversely, the NPS proposed to reserve this land as a river monument solely for recreational use. Along with the dam controversy, NPS and the FS proposals divided the local communities. Bruce Elliot (2 Apr. 1998), an ex-FS member of the Mark Twain National Forest, acknowledged in his oral history interview that there was a rivalry between the two federal agencies. Consequently, many local individuals became the chess pieces in this governmental competition for the rivers.

Locals like Leo Drey were strong supporters of the USFS proposal because it would perpetuate the use of the land for harvesting profitable timber. Leo Drey was a prominent landowner in the Ozarks and continually fought against the sanctioning of the rivers for recreational use. He believed that the FS would do a better job than the NPS because the former has been present in the community long before the river proposals and maintained a good rapport with the locals (Flader, 2011). Drey’s ideology called for the preservation of the “Pioneer Forest” concept, which advocated for the free use of the land for those who first settled there (Sarvis, 2002). Culturally, the “Pioneer Forest” ideology exemplifies the independent, endogenous ethos of the Ozark people. On the whole, local culture evolved to become an integral component for gaining political leverage for the various sides of each controversy.

Despite the opposition of prominent locals like Leo Drey, the NPS did not go without garnering support. James Grassham, who served 16 years as mayor of Van Buren, Mo., favored the Park Service plan over the FS proposal. As indicated through his interview, Grassham (1 Apr. 1998) felt that the NPS could do a better job of preserving the integrity of the landscape and the rivers through a recreation-based approach rather than a timber-based one. Overall, there was never a complete consensus over who should have control over the Riverways. These competing forces remained until 1964, when President Johnson authorized the Current and the Jacks Fork Rivers under the watch of the NPS. Four years later, the FS managed to gain control over the Eleven Point River through the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (Sarvis, 2002).

The Passage of the Scenic Rivers Act: Land Acquisition and Eminent Domain

On 27 August 1964, the Ozark National Scenic Riverways was authorized through Public Law 88-492 (Stevens, 1991). Technically, the park was established in the 1970s, after the land acquisition took place. This interpretation was made by David Thompson (20 July 1998), the third ONSR superintendent who saw the park area grow from 15 acres to over 70,000 acres during his tenure. As Park Service employees and locals later learned, this process would not be easy. Land acquisition would turn out to be a drawn out, piece-by-piece battle between the locals and the government. Legal issues over land acquisition, eminent domain, and conservation easements bombarded a landscape already ridden with power struggles and controversies.

Landscape as Wealth: Land Acquisition of National Parks

Little could have been foreseen about the future difficulties that the Park Service or the locals would face. During the primary land acquisition period of the 1960s and 1970s, the federal government was confronted with the first time that it had to section off an area that was 84% privately owned (A Proposal, 1960). Land ownership constituted wealth for the Ozark people. And the government was trying to take it away from them (Sarvis, 2002).

The 1960s and 1970s marked a shift in focus for how the federal government acquired and managed new national parks. Before 1959, most of the land that Congress set aside for national parks was already owned by the federal government. The questions of Congressional limits to buy or condemn private land began with the establishment of two national parks: The Minute Man Historical Park in 1959 and the Cape Cod National Seashore in 1961 (Hemmat, 1986). Like the Riverways, the land that was acquired for these parks was mostly private ownership. Therefore, government naïveté prevailed during the acquisition of private lands for national parks.

Much of the current legal scholarship criticizes the seemingly limitless powers of Congress in private land acquisition. Ragsdale (1991) explains that the breadth of Congress’ land acquisition power is held in the Commerce Clause, the Property Clause, and the Takings Clause of the Constitution. In Article I, Section 8, the Commerce Clause allows Congress to regulate the market as well as the country’s navigable waters. This Clause becomes particularly important with the ONSR controversies over what can go up and down the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers.Under the Property Clause, in Article IV, Section 3, Congress has the authority to oversee and regulate federal lands, even without the consent of the states that encapsulate the property. Further, Congress’ power was augmented under the Property Clause through the landmark case, Kleppe v. New Mexico, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could exceed its limitations to adjust or create rules on proper land use (Shepard, 1984). Regarding the situation of the ONSR, the Kleppe decision symbolizes the groundwork for the mistrust of Congressional powers.

Finally, the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment states that the government may take on private property through payment or just compensation. With that said, scenic easements were a popular way for private landowners to keep their land by adhering to government-proposed land-use regulations. In extreme cases, eminent domain would be exercised if a consensus on payment was not reached and the land was necessary to the goals of the federal government (Ragsdale, 1991). Under the stated constitutional clauses, the power of the Congress augmented fear for local private landowners on the Riverways when the ONSR became established. Overall, the Commerce Clause, the Property Clause, and the Takings Clause justified Congress in the Riverway land acquisition, all the while stirring up one conflict with the affected locals.

Land Acquisition: Clash between Locals and the Federal Government

Characteristic of their culture, Ozarkans typically do not like to be told what to do with their land (Thompson, 20 July 1998). Philosophically, their view of the landscape can be traced to the writings of John Locke, which advocated the presence of non-privatized commons areas for the first individuals to settle in an area. The belief system argued that people had the right to settle on a piece of land and use it to make a living without the government declaring it (Ragsdale, 2013).

For the most part, the “Lockean” ideology likens itself to the communal Scotts-Irish ancestry of the Ozark peoples. Such an intimate connection to the landscape conflicted with the government-sponsored, free-market competition that would soon overcome the area. The locals responded by gathering in groups, attending hearings, and posting anti-ONSR signs like “Monument No” and “No Park Service Employees Welcome” (Sarvis, 2002). Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998), a past ONSR superintendent, added that “it was so difficult to get anything done, particularly seeing that there was always a small core of local people that would object to any plan that the Park Service would come up to.” The government’s premise was to preserve the land for future generations of Americans (Ragsdale, 1994). Evidently, the Ozarkans believed that their culture had already preserved the landscape through maintaining traditional practices without government intervention.

Specifically, the lack of communication and understanding intensified the clash between the locals and the government was the. David Thompson (20 July 1998), who saw the ONSR grow from 15 acres to 70,000 acres during his employment as the superintendent, admitted that locals had not been told the exact truth about the land acquisition process. For example, Thompson said that scenic easements contained countless regulations that were difficult to follow, such as how far to build one’s house from the river or what type of materials to use to build it. Moreover, Thompson cited a disconnection between the ONSR park attendants, of whom he was a part, and the separate Land Acquisition Office. In consideration of the land acquisition controversy, Thompson stated:

It’s hard when you’re getting it second and third hand to really put a finger on exactly what they were telling them. Because you don’t know how much shading the people were giving…But I think they felt they would be offered a price that was probably nowhere near what the land was worth. And if they didn’t accept it, it would be condemned. Well, that was not the case at all. …The only places that would be condemned would be those places that were absolutely needed for development. All of the others we would buy in fee simple if they wanted to sell. If they did not, we would offer them life tenure…But the land was always, in my estimation, fairly appraised.

As a result, the lack of communication affected the local perception of the land acquisition process. Moreover, the fact that the Park Service leadership changed hands frequently provided little room for NPS leaders to build trust with the locals. Don Yantis (31 Mar. 1998), a local Ozark business owner, supported this sentiment by saying that no one who has worked for the National Park Service would be able to legitimately explain the local perspective of the matter. Yantis’ words reflect the perceived disconnect between the locals and the government employees.

For that reason, the NPS was met with hostility by the locals during the land acquisition of the 1960s and 1970s. Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998), park superintendent from 1976 to 1995, spoke from experience when he said that “anytime you get into land acquisition, particularly if you do not have a willing seller and condemnation is used, that creates hard feelings that could last for generations.” To illustrate, Don Yantis (31 Mar. 1998) once sued the NPS when he was told that the government was going to take his land.

He mentioned that the federal government offered him around $1,000 or $2,000 for his property, which he thought was “ridiculous.” Up until the interview in 1998, Yantis owned only a portion of his original property and had to give up about 70 acres to the ONSR. On another occasion, David Thompson (20 July 1998) recalled when the Park Service accidentally destroyed and burned a local individual’s house because the NPS employees mistook that parcel of land for the one that was actually purchased. Accordingly, the lack of communication, the constant turning over of NPS employees, and the pitfalls of the land acquisition contribute to the problematic landscape of the Riverways.

Local Loopholes in the Federal Land Acquisition System

Despite the looming land acquisitions, many Ozarkans discovered ways of keeping their riverfront properties. The federal government was often outfoxed by prominent Ozark locals with political contacts. Private landowners found loopholes around the takings process and managed to retain most, if not all, of their land. Leo Drey was one of those people. According to Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998), park superintendent from 1976 to 1995, Drey saved his land by holding the government off through the use of his network of political connections. Additionally, according to David Thompson (20 July 1998) and Don Yantis (31 Mar. 1998), other less-connected locals settled with scenic easements or made an agreement with the NPS to turn over their land when they died or decided to sell.

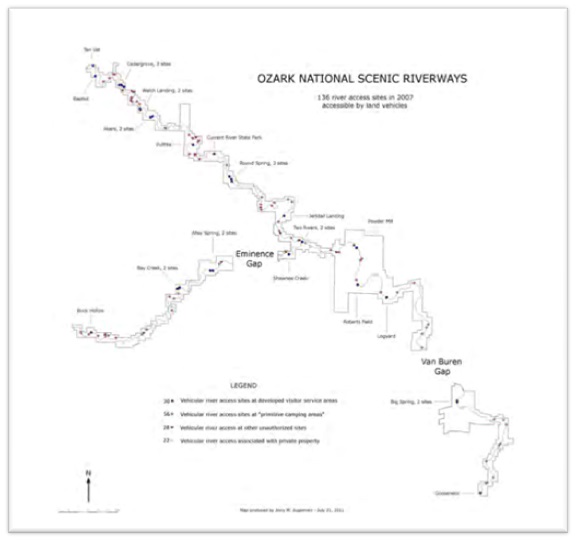

How the ONSR Got its Shape, or Lack Thereof

The period of land acquisition included essential events for how the Riverways were shaped. For example, the lack of federal funding for the NPS led to inadequate land surveys. Therefore, the maps that display the ONSR do not necessarily reflect the actual park boundaries. In other words, the pixelated property of the ONSR is mostly arbitrary because the park perimeter has never been fully surveyed. Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998) revealed that the NPS used to “scrape up a few thousand bucks” and “run a survey on just a segment of part of a boundary to resolve a specific controversy.” At the time of the land acquisition, David Thompson (20 July 1998) observed that park law enforcement became almost impossible because of the arbitrary boundaries. Thompson explained that “with the Riverways spread out so far and with the checkerboard land pattern that [the NPS] had during the time, it was very difficult to know when you were on [ONSR] property or not.” In effect, controversies arose over how land was acquired, delineated, and enforced.

The map in Figure 8 best exemplifies the geographic problems with how the ONSR was formed. For example, there are two gaps represented in the map: The Eminence Gap and the Van Buren Gap. Recognized by the Ozark Riverways Act, these void spaces in the park boundaries allowed for the autonomous development of the towns of Eminence and Van Buren (Stevens, 1991). Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998) added that Congress issued an intentional four-mile gap between Van Buren and Eminence outside of National Park jurisdiction, which explains the appearance of dispersion on ONSR maps. These gaps can be construed as a compromise between the federal government and the local communities over land disputed.

Furthermore, key political actors and well-organized groups of locals were responsible for why some places were excluded from land acquisition. Ripley County, south of Van Buren, provides a relevant example of political maneuvers to shape the ONSR landscape. Congressman Paul Jones, for instance, managed to keep Ripley County from becoming part of the finalized Riverways plan, despite the county being included in the first proposal. As explained by Bill Wright (5 Aug. 1998), Jones was instrumental in the fact that the Riverways boundaries “stopped” at the north Ripley County line.” In retrospect, Congressman Jones was regarded as one of the most influential political powers in the boundary shaping of the riverways (Bill Wright, 5 Aug.

1998).

Strength in numbers also gave weight the Ripley County exception and the overall formation of the park boundaries. Along with the influence of Congressman Jones, the exclusion of Ripley County from the final plan was aided by four or five Greyhound buses of Ripley County citizens that attended the primary hearing in Newport, Arkansas. As a result, Ripley County, Wright said, was eligible for land acquisition in the 1961 Park Service Bill but not in the 1963 final product.

Along with the Ripley County controversy, the strength of local groups also determined the location of the ONSR headquarters. According to Bill Bailey (20 Apr. 1998), Eminence should have been the main headquarters for the Riverways because of its central location near the intersection of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. But, Van Buren became the headquarters because over 150 Van Buren citizens attended the hearing over the issue, while only one man turned up from Eminence. Hence, the successful use of strength in numbers account for why many geographic aspects of the ONSR, such as the headquarters, do not make logical sense.

Post-ONSR Establishment: The Effect of the Riverways on the Ozark Community

Since its establishment, the creation of the ONSR has assisted in the development of local infrastructure and businesses. Locally-run canoe rentals dominate the riverscape and funnel money into the economies of Eminence, Van Buren, and the adjacent areas (Hall, 1969). Annually, millions of tourists make pilgrimages to this national park for floating, canoeing, kayaking, camping, and fishing (Sarvis, 2002). Markedly, the economic geography of the Ozark community seems to have been expanded due to the introduction of the national park (Stynes, 2011).

Throughout the years, a gradual change has appeared in the Ozark culture from fear of the ONSR on their traditional ways of life to a partnership with the NPS. To illustrate, David Thompson (20 July 1998) recognized that one of his major accomplishments as superintendent was “getting acceptance as much as possible by the people, and smoothing the feathers of the people that ran the johnboats, canoes, and so forth; to try to work that out to where they could live together.” These words signify a long-earned trust of the NPS employees at the ONSR.

However, controversy has still ensued at the Riverways, even after the period of land acquisition. Regulation and management of the ONSR has been challenged by the congestion of tourists and the pervasive traditions of the Ozark river populations. The congestion is largely influenced by highways that allow for easier access to travelers by automobile (See Figure 9). Other conflicts include but are not limited to regulations on motorboat horsepower, canoe concessionaires, wild horses, grandmawing, and trapping.

| Figure 9: Road Map of the Ozarks (River Use Management Plan, 1989) |

The increased presence of jet boats caused has angered many locals over the years, such as Don and Pauline Yantis (31 Mar. 1998). Don and Pauline lament about the disruption of motorboats on the preservation of the riverscape environment and atmosphere. Similar complaints have been spanned over half a century in other national parks, like Yellowstone (Yochim, 2011). Around 1977, Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998) noted that the propeller-driven johnboats were outnumbered by the popular jet boats, which had motors that were loud and overpowered the watercrafts of the other recreational users. To provide a solution, Sullivan said that horsepower restrictions were imposed on the different parts of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers. On the Upper Current and Jacks Fork, where floaters and canoeists were most prevalent, horsepower was limited to lower levels, while the Lower Current allowed for jet boats of higher horsepowers (Sarvis, 2002).

Also, the increased presence of unlicensed canoe concessionaires caused tension among locals, outsiders, and the Park Service. Canoe-renters, both formal and informal, were unequally distributed, with most of concentrated on the heavier-trafficked Upper Current. The number of non-permitted canoe concessionaires correlated with the rise in the number of float trips, which skyrocketed from 40,000 in 1968 to 295,000 in 1979 (Sarvis, 2002). Overcrowding resulted from the inability to regulate the number of boats that concessionaires rent out. Arthur Sullivan elaborated that the private sector benefits the NPS management of the Riverways through canoe concessionaires, as well as providing motels, hotels, and restaurants for the area. But, the informal canoe businesses impaired the NPS on the ability to regulate them. Arthur Sullivan (15 July 1998) detailed the long legal battle raged on for years until the NPS finally won the ability to enforce canoe permits in the 1980s.

In recent decades, emotional debates have been kicked up over whether or not to remove a group of feral horses that live in the ONSR boundaries. The government perceived the animals as not having a legitimate place at the ONSR because they were non-indigenous species of the area. However, opposition has come from locals, especially the Missouri Wild Horse League (Rikoon, 2006). Congress ended up passing the 1996 Omnibus Parks and Public Lands Management Act, PL-104-333, to keep the feral horses on the park lands (Sarvis, 2002). To this day, the debate over the management of the feral horses continues to inflame local communities.

Finally, the ONSR was perceived as a threat to the regional traditions of the grandmawing (stealing standing timber) and trapping. Locals were often at odds with the federal park prohibitions on these two aspects of Ozark culture. Grandmawing continues to this day, though it remains illegal. Trapping, however, was originally prohibited but is now allowed on ONSR land though a 1987 court decision (Sarvis, 2002). Together, grandmawing and trapping represent two distinct Ozark traditions that the NPS had to accommodate for the ONSR.

Understanding the Present

Currently, the ONSR faces a series of dilemmas. Pollution and inadequate management of the Current and Jacks Fork Rivers led to it being recognized by American Rivers as one of the United States’ ten most endangered rivers of 2011 (Flader, 2011). Not only is the NPS challenged by environmental issues, but the agency has fallen victim to the bipartisan controversy surrounding the 2013 Affordable Care Act. The ONSR and the affected community suffered economically when the 401 national parks were closed for two weeks due to the 2013 federal government shutdown. The federal piece of land that proved vital to the function of some Ozark towns suddenly became dormant, which sent financial shocks to the pockets of Ozark business owners who relied on the Riverways. Eugene Maggard, a 72-year-old general store owner, observed that the ONSR was being wielded as a “political tool” rather than a tourist destination (Bogan, 2013). Instead of the 1960s “Monument No” signs, the Riverways displayed notices that said “Closed” (Testa, 2013). Overall, the ONSR’s present situation is characterized by tough economic and political challenges.

Future Insights and Predictions

In the midst of the shutdown, the contemporaneous publication of the Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement (2013) has sparked renewed interest in revamping the future management of the national park. However, the historical geography of the ONSR makes the sobering case that a quick solution is doubtful. Using the words of Sarvis (2002), the ONSR is faced with a difficult legacy for the future of its lands, employees, and associated communities. Controversies over the ecology, culture, territoriality, and politics have remained ever-present since the organization of the Riverways. It is unlikely that these problems will ever be eliminated.

However, these managerial “snags” can be reduced in impact through various ways. Ragsdale (2012) suggests that national park leaders take time to reflect on the goal of adopting a sustainable system of land management before setting up a step-by-step strategic plan of execution. The ONSR is making the first leap into the process by drafting a new management plan. Further, in another article, Ragsdale (1994) highlights the importance of accepting responsibility of the consequences for all park decisions, good or bad. With its long history of conflict, the ONSR and the NPS could benefit from becoming more accountable and determining how to proceed more effectively.

Also, Dressler et al. (2006) acknowledges the trend of developing nations to decentralize national parks in order to foster a community-based conservation approach. Kaltenborn et al. (2011) found similar successes in the Dovre-Sunndalsfjella National Park in Norway. Shown to be effective in the Philippines and in Norway, the local approach to national parks could work in greater harmony with the culture of the Ozark community, which has historically tended to be xenophobic of outsiders (Sarvis, 2002).

In sum, the ONSR would become more prosperous if the NPS relied upon the knowledge of local communities that have lived in the area for generations. The oral histories of the Ozark Riverways present a wealth of information that locals contain about the inner workings of the park’s history. Also, national park governance over the ONSR should become more decentralized to give locals more weight in decision-making. This approach could smooth over a lot of the communication snags between federal and local powers, as well as foster better decision-making in future years. For these reasons, a more locally-based solution could change the image of the ONSR from a political prop to a sustainable preservation area.

Reference List

A Proposal: Ozark National Scenic Riverways (1960). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Bird, R. (2009). Reviving necessity in eminent domain. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 33(1), 239-281.

Bogan, J. (2013, October 7). Southern Missouri river towns struck by shutdown. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved October 10, 2013, from http://www.stltoday.com/news/state-and-regional/missouri/southern-missouri-river-towns-struck-by-shutdown/article_f2d9e6a0-b870-5c1d-982f-8a0d57906d2f.html

Denevan, W.M. (1992). The pristine myth: The landscape of the Americas in 1492. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 82(3), 369-385.

Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement. (2013). Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Dressler, W. H., Kull, C. A., & Meredith, T. C. (2006). The politics of decentralizing national parks management in the Phillipines. Political Geography, 25(7), 789-816.

Flader, S. (2011). A Legacy of neglect: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways. The George Wright Forum, 28(2), 114-126.

Gross, A. C., Poor, J., Sipos, Z., & Solymossy, E. (2009). The multiple mandates of national park systems. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 5(4), 276-289.

Hall, Leonard (1969). Stars Upstream: Life Along an Ozark River. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Harlan, J. (2010). Tracing the ‘ghostly footprints’ of the landscape. Missouri Natural Areas Newsletter, 10(1), 2-3.

Hemmat, S. (1986). Parks, people, and private property: The National Park Service and eminent domain. Environmental Law, 16(4), 935-961.

Kaltenborn, B. P., Qvenild, M., & Nellemann, C. (2011). Local governance of national parks: The perception of tourism operators in Dovre-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Norway. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 65, 83-92.

Lynott, M. J. (1991). Round Spring archaeology, Ozark National Scenic Riverways. Lincoln: United States Department of the Interior.

Meinig, D. W. (1979). The Beholding Eye: Ten Versions of the Same Scene. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays (pp. 35-47). New York: Oxford University Press.

Meinig, D. W. (1989). Continental America 1800-1915: The view of an historical geographer. The History Teacher, 22(2), 189-203.

O’Brien, M. J. and Wood, W. R. (1998). The Prehistory of Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Painter, J. (2010). Rethinking Territory. Antipode, 42(5), 1090-1118.

Ragsdale, J. W. (1991). The principles, tools, and limits of preservation law in Missouri. UMKC Law Review, 60(2), 195-226.

Ragsdale, Jr., J. W. (1994). The Buffalo River: A jurisprudence of preservation. Environmental Affairs Law Review, 21(3), 429-481.

Ragsdale, Jr., J. W. (2012). The nutty putty cave, the zen runner and other allegories about life, death, value and law. UMKC Law Review, 61, 1-76.

Ragsdale, Jr., J. W. (2013). To return from where we started: A revisioning of property, land use, economy and regulation in America. UMKC Law Review, 81, 1-103.

Rikoon, J. (2006). Wild Horses and The Political Ecology Of Nature Restoration In The Missouri Ozarks. Geoforum, 37(2), 200-211.

River Use Management Plan: Ozark National Scenic Riverways. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1989. Print.

Sarvis, W. (2013). A difficult legacy: Creation of the Ozark National Scenic Riverways. The Public Historian, 24(1), 31-52.

Sauer, C. O. (1941). Foreword to Historical Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 31(1), 1.

Shepard, B. (1984). The scope of Congress’ constitutional power under the property clause: Regulating non-federal property to further the purposes of national parks and wilderness areas. Environmental Affairs, 11(3), 479-538.

Schuchard, Oliver (1984). Two Ozark Rivers: The Current and the Jacks Fork. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Stynes, D. J. 2011. Economic benefits to local communities from national park visitation and

payroll, 2010. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2011/481. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Testa, K. (1996, April 29). Camping’s out: National parks forced to cut back. St. Louis Post-Dispatch (pre-1997 Fulltext), p. 1. Retrieved October 10, 2013, from the ProQuest database.

Yochim, M. J. (2011). Yellowstone City Park: The dominating influence of politicians in National Park Service policymaking. The Journal of Policy History, 23(3), 381-398.

Oral Histories

Yantis, Pauline. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 31 Mar. 1998.

Yantis, Don. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 31 Mar. 1998.

Grassham, James. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 1 Apr. 1998.

Elliot, Bruce. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 2 Apr. 1998.

Bailey, William. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 20 Apr. 1998.

Sullivan, Arthur. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Phone interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 15 July 1998.

Thompson, David. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Phone interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 20 July 1998.

Dix, David. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 5 Aug. 1998.

Wright, Bill. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 5 Aug. 1998.

Braschler, Gene. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 21 Aug. 1997.

Braschler, Gene. Interview by Will Sarvis. Transcript. Personal interview. The Oral History Program of the State Historical Society of Missouri. 5 Aug. 1998.