Published on Aug. 2, 2014

All cultures of the world find explanations for death and the afterlife. In the Christian faith, when believers of Jesus Christ and his Holy Father perish, they will have everlasting life in Heaven. In the Hindu faith, it is believed that when one dies, he or she will resurrect into a new form. Death scares humans, so we try to find ways to explain it and make it seem less frightening. The ultimate truth, however, is that no one can truly define what happens after the death of the body. Many artifacts available in the African art collection of the University of Missouri Museum of Art and Archaeology were used in the burial of men and women, and they provide us with an interesting look at the concept of death in early African societies.

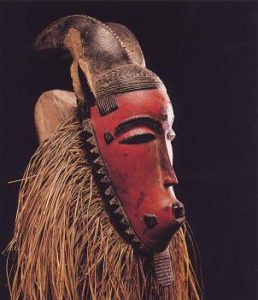

One artifact in particular stands out from the rest. It is an Igbo mask used to speak to ancestral spirits by one of their masquerades. In Chinua Achebe’s novel, Things Fall Apart, we learn that the Igbo speaking people of Southeast Nigeria believed that the ancestral spirits and the spiritual world in which they lived were directly linked to the world of the living. They believed that death was not the end of the spirit’s journey. This mask clearly supports that idea. According to Igbo traditions, ancestors constantly watched over their descendants from the spiritual world. As a consequence, descendants had to please their ancestors or otherwise be cursed (Achebe, 1994, p. 122). Masquerades allowed the people to speak to their dead ancestors using masks similar to the one available at the Museum of Art and Archaeology. These masks were made of wood and would be worn during traditional masquerade ceremonies.

The mask displayed at the museum depicts a young male ancestral spirit or an animal spirit. The Igbo had a very complex religion, especially when it came to death and the afterlife. Christians, who would later appear in Africa, saw the Igbo as primitive in their beliefs, even though many of them believe in ghosts and angels who can speak to us. The Igbo of early Africa, however, were not that different, except that they believed that their ancestors’ spirits were all around them and that they had to be pleased. The masks and masquerades provided the Igbo with a way to speak to their ancestors just how Christians pray to God, seeking advices and asking for a good harvest. Okonkwo, Achebe’s main character in Things Fall Apart, for example, threatens his sons by saying that his ancestral spirit will haunt them for all their days if they converted to Christianity, indicating how deeply the belief of pleasing your ancestors was embedded into Igbo society (Achebe, 1994, p. 172).

In conclusion, masks such as the one available at the Museum of Art and Archaeology allow us to further understand the belief systems of early African societies. Africans were just like all other people in the world in their effort to understand death and the afterlife. These masks show us that Africans, such as the Igbo speaking people, wanted to speak to their ancestors and seek their approval. They also show us aspects of their religion. The Igbo, for example, believed that good harvests and a good afterlife would come only if they pleased their gods and ancestral spirits, but they could achieve this aim only with the help of masks and masquerades. All in all, the mask at the museum is not just a mask, but also a portal to Igbo culture and religious beliefs.

Reference List

Achebe, C. (1994). Things fall apart. New York: Anchor Books.