Published on July 12, 2021

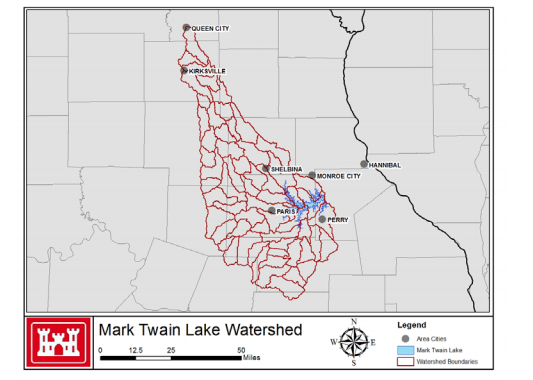

In Northeastern Missouri, the Mark Twain Lake Watershed covers 2,318 square miles (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality). This watershed, shown in Figure 1, provides drinking water, water for crops and livestock, fishing, beaches, and water for boating and canoeing (Missouri Department of Natural Resources).

However, within this water and surrounding soil, a chemical called atrazine, an herbicide commonly used to exterminate broadleaf weeds that are plentiful in corn and sorghum crops. According to the Missouri Department of Agriculture, there are 95,320 Missouri farms, each with an average of 291 acres of land (“Missouri Ag Highlights”). In Missouri, 23.8% of farms produce sorghum and another 18.4% produce corn which are the two most commonly harvested crops in the area surrounding the Mark Twain Lake Watershed (“Missouri Ag Highlights”). Atrazine is the second most popular herbicide choice in the United States and is also popular in Northeast Missouri because it is readily available through local retailers such as Lowes and Walmart as well as industrial retailers and farming cooperatives (“EPA Administrator Wheeler…”).

The herbicide is commonly sold as a fine white powder and is insoluble in water (Nat’l Center for Biotechnology Information). To follow Missouri regulations for atrazine, farmers apply atrazine in similar amounts to both corn and sorghum fields, at a maximum of 2.5 pounds of active ingredient per acre annually (Bradley, Kevin W., et al.). After application, rain causes runoff of the atrazine into Mark Twain Lake and the watershed. Thus, those who live in the watershed are indirectly responsible for polluting their water as they are the ones who use atrazine in their fields. For the local population, the Clarence Cannon Wholesale Water Commission provides drinking water from Mark Twain Lake for 72,942 people who spread across fifteen cities, fourteen counties, and nine water districts (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Clarence Cannon Dam and Mark Twain Lake). Currently, there are propositions put forth by local and state institutions to limit the amount of atrazine found in the watershed and soil, but there are no immediate solutions to atrazine pollution.

Water Quality Section – Water Quality; Used with permission from USACE, Mark Twain Lake)

Some organizations such as the United States Department of Agriculture, United States Army Corps of Engineers, Missouri Department of Agriculture, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and other federal institutions are engaged in plans to attempt to reduce the amounts of atrazine found in the Mark Twain Lake watershed. The government is aware of these issues; through government initiatives, such as the 1972 Clean Water Act, samples are taken from a variety of locations throughout Mark Twain Lake every two years and reported back to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality). There are three water quality classifications for the state of Missouri; below 3 μg/¹ in drinking water is an acceptable level, 82 μg/² is considered acute, and 9 μg/³ and above is severe (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality). During the 2018 fiscal year, the last year of complete data, Mark Twain Lake was sampled at eleven locations, as shown in Figure 2, within the lake at different times of the year, resulting in forty-three test points. Of these forty-three test points, only ten were below 3 μg/¹, resulting in what can be perceived as safe-drinking water, leaving the other thirty-three test points as unsafe to drink (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality). In addition, according to the Water Quality Report published in 2018 by the Water Quality Section of the St. Louis District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, not one of the test locations consistently remained below the recommended three parts per billion (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality). Instead, the average atrazine concentration in Mark Twain Lake for the 2018 fiscal year was 5.88 μg/¹, which is not considered safe drinking water by state standards (United States, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Environmental Water Quality Section – Water Quality).

The reason testing is done in Mark Twain Lake is because it can have serious consequences on the public and environment. The symptoms of atrazine poisoning can be as common as diarrhea and vomiting, irritation of the eye and mucous membranes, abdominal pain, and skin reactions such as rashes (Cornell University et al.). Some of the long-term side-effects for newborns include birth-defects, low fetal weights, and urinary system and limb defects (“Public Health Statement for Atrazine”; Freeman et al.). Other side-effects for adults with lifetime exposure can include damage to the liver, kidneys, and heart, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, as well as increased risks of ovarian and prostate cancer (“Public Health Statement for Atrazine”; Freeman et al.). In a pesticide information profile compiled by Cornell University et al., atrazine was found to be absorbed into the bloodstream through skin contact, inhalation, and ingestion if one ignores safety precautions (Cornell University et al.). Due to the ease at which exposure can occur, those of farming backgrounds are more susceptible to atrazine exposure, but atrazine still indirectly impacts the general population.

Environmentally, atrazine harms wildlife such as leopard frogs that are native to the Midwestern United States. A study completed by Hayes et al. of the University of California Berkeley found that frogs exposed to atrazine turn into hermaphrodites where they show both male and female reproductive behaviors (“Popular Weed Killer Demasculinizes Frogs…”). Additional research done by Hayes et al. showed male frogs exposed to atrazine produce one-tenth of a normal level of testosterone, produce eggs in their testes, and have smaller vocal cords (“Popular Weed Killer Demasculinizes Frogs…”). The level of testosterone produced is so low, that unaffected female frogs produce more than the male frogs exposed to atrazine (“Popular Weed Killer Demasculinizes Frogs… ”). There is evidence that suggests atrazine is also toxic to some birds such as mallard ducks, bob-white quails, and ring-necked pheasants, all of which are native to Missouri and commonly hunted fowl (Cornell University et al.). Atrazine is proven to be harmful to the classification of whitefish, which includes bass and other freshwater fish, where atrazine accumulates in the brain, gut, gallbladder, and liver (Cornell University et al.). In Northeastern Missouri, hunting and fishing provide a source of food and doubles as a recreational activity. Thus, not only is atrazine found in the drinking water, but it is also in the animals eaten by those who hunt and fish locally.

There are current propositions to reduce the amount of atrazine in the soil and the water supply with varying success. The local preventative measures are led by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, the Missouri Department of Agriculture, and the Clarence Cannon Wholesale Water Commission (“From Field to Faucet…”). One of the most common methods to combat atrazine runoff is to increase vegetative buffers at the edges of fields by maintaining at least 50 feet between the edge of a border and the field drain or stream (“From Field to Faucet…”). Farmers implement this practice through natural plot borders such as sections of trees and other natural barriers between fields. Other methods include not tilling the soil after atrazine application, waiting to apply until no rain is forecasted, and only spraying as needed (“From Field to Faucet…”). In addition, not applying atrazine in poor weather will reduce the chance of runoff, and increase the effectiveness, leading to later requiring less atrazine being dispersed postemergence of the crop to ensure a similar rate of success. The atrazine present will become more effective at killing off surface-level broadleaf weeds if farmers choose not to till the soil after application. For postemergence, which is when the crops have sprouted and grown to about 12 inches tall, farmers can mix atrazine with other herbicides, which increases the effectiveness and lessens the amount required up to 67% (“From Field to Faucet…” ). There is also a recommendation put forth by the Clarence Cannon Wholesale Water Commission to follow the herbicide label and to not mix the compounds within 50 feet of a well or water source (“From Field to Faucet…”). The Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) and the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS) offer incentives through cost-share programs to help landowners build buffers, plant field borders, filter strips, and cover crops (“From Field to Faucet…”). This program covers up to 75% of the installation cost and provides incentives ranging from 30 to 1,200 dollars per acre (“From Field to Faucet…”). These incentives not only benefit the environment and ecology of the area, but also the farmers themselves. This allows farmers to receive the reimbursement and incentive as well as the health benefits of the reduced atrazine concentration in the drinking water.

There is one proven method that does reduce the amount of atrazine present in the drinking water, but it comes at the expense of the environment. Water treatment facilities can add an expensive powder-activated carbon to reduce the atrazine present to levels below three parts per billion (“From Field to Faucet…”). The issue with this method is the powder-activated carbon can make it into the water, causing algal blooms leading to bad water quality, musty-tasting water, and unsafe cyanotoxins (“From Field to Faucet…”). Cyanotoxins over a period of exposure to humans can cause death or severe symptoms such as colorectal cancer, liver damage, liver cancer, and gastroenteritis (Bláha, Luděk, et al.). Animals experience similar symptoms to humans due to cyanotoxin exposure (Bláha, Luděk, et al.).

This problem – the atrazine found in the Mark Twain Lake Watershed – is serious because the general public may be unaware the water supply is tainted and potentially poisoning them. According to the 2018 Water Quality Report published by the Water Quality Section of the St. Louis District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, only ten of the forty-three atrazine concentration tests were within a safe range for drinking water. For 2018, the average concentration of atrazine in Mark Twain Lake was found to be 5.88 parts per billion, which is not considered safe for consumption. The ecological impacts are also present and are visible in the leopard frogs in research completed by Hayes et. al., where male leopard frogs exposed to atrazine became hermaphrodites. In the data collected by Cornell et. al in the instances of wildlife native to Northeast Missouri, there is evidence of the harmful impact atrazine has on native populations. With atrazine present in both water and potential food sources, the issue becomes much more dangerous. Even though there are preventative methods, they are just that – preventions, not solutions. The only proposed solution is powder-activated charcoal. The issue with this solution is it can release cyanotoxins into the drinking water that would poison both people and animals, eventually leading to death. In order for change to occur, people must be made aware of the danger they face from the water they drink to the animals they eat and then act on that awareness to create a positive outlook. In summary, I feel atrazine is a threat to my home, as I live within the Mark Twain Lake Watershed and drink the water provided by the Clarence Cannon Wholesale Water Commission. This is a concerning issue because it not only involves me, but my community. Knowing what I know now, I plan to educate my friends and neighbors on this serious situation. Perhaps as a group, we can find a way to work with the Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) and the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS) to implement additional alternatives to keep our families safe, and our environment healthy.

My name is Kayla Spence and I am a sophomore at the University of Missouri’s Honor College pursuing a double major in Biological Sciences – BS and Psychology – BS with a minor in Computational Neuroscience. I was recognized on the Dean’s List for the College of Arts and Sciences and I am a member of the Mizzou ASL Club and MU Women in STEM. My future plan is to continue my education at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and use this education to become a neurosurgeon to help those in need achieve a better quality of life. My personal goal is to raise awareness surrounding the potential and current atrazine pollution of the main public water source at Mark Twain Lake, thus improving the well-being of the population, and ultimately enhancing quality of life.