Published on June 26, 2019

Americans wound down Halloween 1938 gathered around their radios to hear Orson Welles read a rendition of War of the Worlds. Far from them snuggling up for a comfortable evening by the hearth, the broadcast sent a ripple of fear gliding across the nation. In the ensuing mania, America revealed its anxiety about the impending loss of its tranquil isolation, and Americans expressed their fears through the monster, the alien attackers in this case. Once awoken from its slumber, the Great Power status of the United States would lay responsibilities at Americans’ doorsteps, and the ever-growing ruckus the world produced made another century of rest impossible for them. The energy released by Welles’ transmission is not especial in America’s history. Instead, it is one of the best lenses into the cultural foundation of the twentieth-century American ascension to global hegemony, a history with which the events of Halloween 1938 cohesively align. The two sections of American history, isolation followed by involvement, were split by the broadcast, and American anxiety about that foreign policy transition from peace to intervention shined through their maniac acceptance of alien invaders.

Under normal conditions, as Eleanor Roosevelt noted, the broadcast would not have brought about a maniac response, but panic ensued under the wartime-fear conditions of the day. In 1939, she said, “[A] sane people, living in an atmosphere of fearlessness, does not suddenly become hysterical at the threat of invasion” (Hoffman 130). To uncover whether or not America’s political climate was revealed in 1938, Roosevelt’s words are an important launchpad. If Americans were indeed thrown into mania by the broadcast, the causes ought to be pursued. Those causes form the roots of nineteenth-century American foreign policy, and Roosevelt’s statement commands investigation.

The political climate was less than sane and far from fearless: Europe was on the brink of World War Two. Hitler had spread Germany’s borders across Austria seven months before the broadcast and annexed the Czech Sudetenland in September, only a month before the broadcast (“Munich Agreement”). Neither was the Soviet Union, the other largest combatant in WW2, adopting a pacifist foreign policy. In the 1930s, its totalitarian leader Joseph Stalin expanded Russian influence into Ukraine, closer to Germany. One and a half million Ukrainian peasants’ properties were confiscated under Stalin in 1930, and four million Ukrainians were starved to death under Stalin’s Death by Hunger subjugation plan (“Holodomor”). Americans listened intensely to these developments, fearing their nation’s entanglement again in a general European war between these two neighboring powers in the same fashion that they hung onto their radios and listened to the story of an unfolding—no matter how fictional—war on their own soil.

The Halloween broadcast had been intended to entertain children, but it also struck a chord among adults. According to Welles, the story was already “familiar to children through the medium of comic strips and many succeeding novels and adventure stories,” and he did not intend there to be any mania (Schwartz). This was a children’s story being read to children and their families, but many adults took real-life action. The New York Daily News reported that at least four thousand Americans had “rushed from their homes” upon hearing the transmission, while a woman in Pittsburg attempted suicide and declared, “I’d rather die this way than like that!” Her husband luckily stopped her (Dixon). A large alien force, Welles told them, had deployed in New Jersey. Despite the military’s efforts, the aliens were raging across the Eastern United States, defeating the sorely under-armed military. Welles read that “seven thousand men armed with rifles and machine guns [were] pitted against a single fighting machine of the invaders from Mars,” who destroyed New York City, leaving “a lean dog running down Seventh Avenue with a piece of dark brown meat in his jaws, and a pack of starving mongrels at his heels” as the only living, visible knickerbockers. The broadcast ended with “nobody’s there, that was no Martian … it’s Hallowe’en” (War of the Worlds). Any reasonable person would have known that what they were hearing was fiction, but many Americans were not thinking reasonably in 1938.

When thrown into an already anxious America, this broadcast wreaked havoc throughout the nation despite five routine interruptions to remind listeners that they were “listening to a CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in an original dramatization of The War of the Worlds” (War of the Worlds). The New York Times reported the following morning that the broadcast “disrupted households, interrupted religious services, created traffic jams and clogged communications systems” and that at least 20 Americans needed medical treatment for shock and hysteria (“Radio Listeners in Panic”). An additional 30 men had rushed into a Harlem police station with their possessions packed and asked to where they should be evacuated. They believed President Roosevelt had warned them of the alien attack over the radio. In Brooklyn, the Police Headquarters received 800 calls about the broadcast that night (“Radio Listeners in Panic”). People were affected by the story, and they would not have reacted like they did if it had not resonated with them and connected with their reality as something plausible.

America’s experience in the nineteenth century consisted of near-complete military isolation, especially when compared to that of the twentieth century. Americans were global spectators, not players. In 1823, President Monroe formalized this isolationist policy and asked Congress “against the interference of the European powers by force in South America, [and] to disclaim all interference on our part with Europe; to make an American cause, and adhere inflexibly to that” (“Monroe Doctrine”). Keeping to this isolationist Doctrine, the military action that summarized the American nineteenth century was one in which US forces landed on the uninhabited Caribbean island of Navassa in 1891 to protect the US interest in guano (Torreon and Plagakis). The US military existed but was confined to a minimal role in the world.

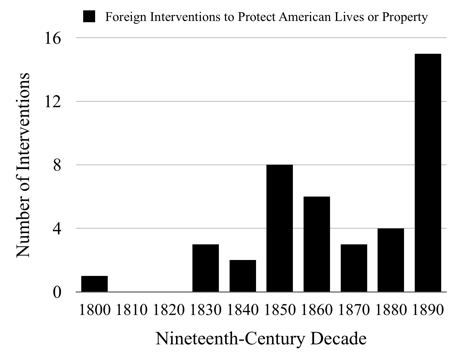

Action was indeed taken to secure Americans’ safety during turmoil in Argentina, Peru, Nicaragua, China, Uruguay, Panama, Colombia, Mexico, Japan, pre-state Hawaii, Egypt, Korea, Samoa, Chile, and the Philippines; but the century was entirely absent of impactful American intervention (Torreon and Plagakis). This record of protecting Americans overseas indicates how difficult it became in an increasingly tumultuous and interconnected world to maintain the Monroe Doctrine. There was a sharp increase in such measures as the century unfolded. More Americans being in more places around the world meant these interventions would become more frequent over time, and America would slowly lose its isolation.

Protests formed around the US’ war with Mexico in 1846, through which the US quickly expanded it borders to the Rio Grande and Pacific Ocean. The War involved only 78,718 US servicemen (DeBruyne), and it happened within North America (“Mexican-American War”). The public was nonetheless enraged by their government going to war. Henry David Thoreau’s words on the matter would have resonated in Hippie counterculture: “I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine.” He was writing about his refusal to pay taxes to the federal government and fund the war effort (“Mexican-American War”). Thoreau was not alone in his opposition to his government’s new expansionism, and the Mexican-American War was also not alone among the nineteenth century’s small but unpopular wars.

More protests came amid the Spanish-American War later in the century. In 1898, the eve of the new century, America sent 306,760 servicemen to defeat the Spanish Empire (DeBruyne). The Anti-Imperialist League was formed to combat this new trend of foreign US involvement. Their Platform began, “We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty and tends towards militarism, an evil from which it has been our glory to be free,” and it went on to demand a straightaway end to the Spanish-American War. Among other notables, Jane Addams, Andrew Carnegie, John Dewey, William James, and Mark Twain all were members, the last of whom wrote heavily against the War (“The Spanish-American War”). Twain wrote in 1900, “I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land,” and he recommended that the government use the skull and crossbones as a flag for its new Philippines colony (“Mark Twain”). He was not only opposing his own government’s policies, he was naming America a pirate that steals the wealth of foreign lands. In doing so, Twain expressed his anxiety around his nation’s increasing role in global politics.

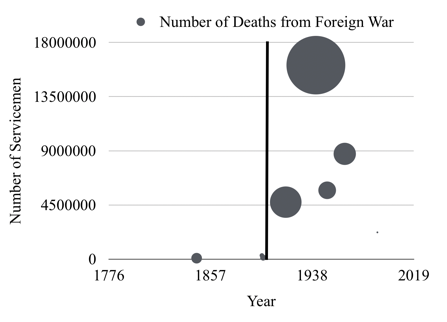

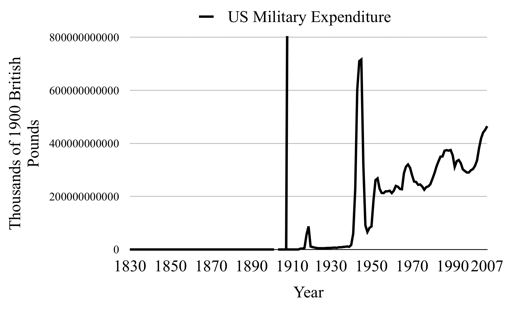

These nineteenth-century wars pale against the wars of the twentieth century. How small the nineteenth century’s wars were should be understood through the upper figure below. The bubbles’ sizes represent the number of American deaths in each foreign war, and the y-axis contains the number of American servicemen in each war (DeBruyne), including the Philippine-American War, which was fought to secure the Philippines colony the US had gained from the Spanish (“Philippine-American War”). Underneath, a figure shows US yearly expenditures on the military. A vertical line represents the year 1900 in both graphs:

There was an explosion in US military involvement overseas once the new century dawned. More than 300,000 American servicemen fought against the Spanish, but nearly 5 million served in WW1. More than 16 million served in WW2 (Roser). A lasting increase in military spending is demonstrated in the bottom figure, which clearly shows an enduring change from a near flat line to an ever-growing mountain. Before 1900, one needs a microscope to discern any spending at all, but the hopping ascent of US expenditures since then is stark. A radical change in US foreign policy is apparent.

That change’s spark came in 1917, when America entered WW1. After his country had made heavy sacrifices, President Woodrow Wilson arrived in Europe to broker a lasting peace. Historian Margaret MacMillan wrote in Paris 1919, “No other American president had ever gone to Europe while in office” (3), and he went to Europe with a “dream of a new world order with the United States at its heart” (6). He presented his Fourteen Points plan to the European powers. Among his demands was that “national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety” and that “[a] general association of nations must be formed” (“President Woodrow Wilson’s”). This hope for peace was sadly dashed when world war broke out again in 1939, the year immediately after Welles’s broadcast.

This time, America had a better shot at global hegemony. MacMillan wrote, “(i)n 1945, the United States was a superpower and the European nations were much weakened. In 1919, however, the United States was not yet significantly stronger than the other powers. The Europeans could ignore its wishes, and they did” (MacMillian). Emerging from WW2 under President Harry S. Truman with a permanently expanded military budget and a newly proven record of foreign involvement, which included dropping two atomic bombs, the United States quickly set up the United Nations in New York City. Under a watchful hand, the post-world-war world took shape. The Truman Doctrine was established in 1947 when President Truman told Congress, “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures,” and his words have guided American foreign policy since (Truman). America’s entry into Korea and Vietnam in the coming years was justified by communism’s containment, which was Truman’s original aim in his address.

Between the World Wars, America found itself at a crossroads. The US Office of the Historian wrote that, despite Wilson’s plead for greater foreign involvement, “the American experience in that war served to bolster the arguments of isolationists; they argued that marginal U.S. interests in that conflict did not justify the number of U.S. casualties” (“American Isolationism”). Marine Corps General Smedley D. Butler warned in his 1935 book War is a Racket that another world war, if it should come, “will be fought not with battleships, not by artillery, not with rifles and not with machine guns. It will be fought with deadly chemicals and gases” (51). Another war did come, but the first sentence’s armaments were in full force. Congress was keen on keeping itself out of another war and passed Neutrality Acts “to prevent American ships and citizens from becoming entangled in outside conflicts” (“American Isolationism”). Despite this struggle, America entered into the War and assumed its place in global politics.

Through the monsters in Welles’ 1938 broadcast, Americans were able to express their anxieties about war. The turn of the twentieth century and WW1 broke the nation’s isolation. The Monroe Doctrine’s barrier dissolved, and Truman’s new policy glowed with atomic fallout for the world to see. In the two decades between the World Wars, many Americans pled for isolation to return, but it never has. Eleanor Roosevelt’s words have been vindicated by history. The panic of 1938 is a symptom that moderns can use to understand the psychological implications impending global hegemony had on America’s citizens, and there is no surprise that Americans acted as they did on the eve of America’s military ascent. The aliens gave them a monster through which to express that friction, and the mania fits snugly in American history.

About Matt Carroll. I am studying History and Spanish as majors at the University of Missouri at Columbia. When I am not engaged in school, I read, write fiction, and study French, German, and Spanish. Last school year, I finished my first novella, and I have started my second already.